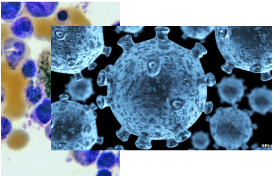

The human immunodeficiency virus

(HIV)

attacks the immune system

The Mississippi child is now two-and-a-half years old and has been off medication for about a year with no signs of infection. More testing needs to be done to see if the treatment - given within hours of birth - would work for others. If the girl stays healthy, it would be the world's second reported 'cure'.

Dr Deborah Persaud, a virologist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, presented the findings at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Atlanta.

"This is a proof of concept that HIV can be potentially curable in infants," she said.

Cocktail of drugs In 2007, Timothy Ray Brown became the first person in the world believed to have recovered from HIV. His infection was eradicated through an elaborate treatment for leukaemia that involved the destruction of his immune system and a stem cell transplant from a donor with a rare genetic mutation that resists HIV infection.

In contrast, the case of the Mississippi baby involved a cocktail of widely available drugs, known as antiretroviral therapy, already used to treat HIV infection in infants. It suggests the swift treatment wiped out HIV before it could form hideouts in the body. These so-called reservoirs of dormant cells usually rapidly reinfect anyone who stops medication, said Dr Persaud. Dr Deborah Persaud, Johns Hopkins Children's Center: "This sets the stage for paediatric care agenda"

The baby was born in a rural hospital where the mother had only just tested positive for HIV infection. Because the mother had not been given any prenatal HIV treatment, doctors knew the baby was at high risk of being infected. Researchers said the baby was then transferred to the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson.

Once there, paediatric HIV specialist Dr Hannah Gay put the infant on a cocktail of three standard HIV-fighting drugs at just 30 hours old, even before laboratory tests came back confirming the infection.

"I just felt like this baby was at higher-than-normal risk and deserved our best shot," Dr Gay said.

The treatment was continued for 18 months, at which point the child disappeared from the medical system. Five months later the mother and child turned up again but had stopped the treatment in this interim. The doctors carried out tests to see if the virus had returned and were astonished to find that it had not.

Dr Rowena Johnston, of the Foundation for Aids Research, said it appeared that the early intervention that started immediately after birth worked.

"I actually do believe this is very exciting.

"This certainly is the first documented case that we can truly believe from all the testing that has been done.

"Many doctors in six different laboratories all applied different, very sophisticated tests trying to find HIV in this infant and nobody was able to find any.

"And so we really can quite confidently conclude at this point that the child does very much appear to be cured."

300,000 HIV-positive babies born in 2011 Better than treatment is to prevent babies from being born with HIV in the first place.

About 300,000 children were born with HIV in 2011 — mostly in poor countries where only about 60 per cent of infected pregnant women get treatment that can keep them from passing the virus to their babies. In the U.S., such births are very rare because HIV testing and treatment long have been part of prenatal care.

"We can't promise to cure babies who are infected. We can promise to prevent the vast majority of transmissions if the moms are tested during every pregnancy," Gay stressed.

The only other person considered cured of the AIDS virus underwent a very different and risky kind of treatment — a bone marrow transplant from a special donor, one of the rare people who is naturally resistant to HIV. Timothy Ray Brown of San Francisco has not needed HIV medications in the five years since that transplant.

A spokeswoman for the HIV/Aids charity the Terrence Higgins Trust said: "This is interesting, but the patient will need careful ongoing follow-up for us to understand the long-term implications for her and any potential for other babies born with HIV."

Previously, antiretroviral therapy is given only once the immune system has been seriously weakened by infection. A trial, in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed that a year-long course of therapy after diagnosis helped preserve the immune system and keep the virus in check. It is thought that early treatment may also reduce the spread of HIV.

The virus is no longer a death sentence for patients who get the best care and drugs. Treatment is given once their CD4 T-cell count, a part of the immune system, falls below 350 cells per cubic millimetre of blood. However, there has been some speculation that starting as soon as a patient is diagnosed may be more beneficial. The Spartac study, which involved 366 patients from eight countries around the world, tested the theory. Questions remain about whether a longer course at an early stage could be more beneficial or whether early treatment should be continued for life”.

Some patients were given 12 weeks of drugs after being diagnosed, another group had drugs for 48 weeks after diagnosis and a third group were given no drugs until they reached the 350 level.

Prof Jonathan Weber, from Imperial College London, said those on the 48-week regime "end up with much higher CD4 cell count and a much lower viral load". "Also, the benefit persists after you've stopped treatment," he added.

Who pays? Keeping a strong immune system is important for preventing other "opportunistic" infections, such as tuberculosis, taking hold. Prof Weber acknowledged that cost was a "massive question" that would represent "a real problem" in poorer parts of the world. However, in richer countries if would mean "only a few extra years" on a lifetime of medication.

Dr Sarah Fidler, also from Imperial, pointed to the benefit of keeping levels of the virus low.

"This could be very important for helping reduce the risk of passing on the virus to a sexual partner," she said. Dr Jimmy Whitworth, from the Wellcome Trust, which funded the study, said: "This study adds to increasing evidence that early initiation of HIV treatment is of benefit to the individual in preventing severe disease and in reducing infectiousness to his or her partners.

"Questions remain about whether a longer course at an early stage could be more beneficial or whether early treatment should be continued for life." However, one of the biggest problems remains identifying people who have been infected. In the UK, one in four people with HIV are thought to be completely unaware they have the infection.

Soucres :

http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/

http://www.cbc.ca/news/world/story/2013/03/03/wrd-us-aids-hiv-baby-cure.html

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-21040256

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-21651225

http://www.who.int/hiv/en/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed